The project on Foresighted Reasoning on Environmental Stressors and Health (FRESH) ran from 2013 to 2014 and investigated the frameworks and evidence base for undertaking integrated assessments of environmental health and well-being.

In the article below, we review how our understanding of the complex links between the environment, human health, and well-being has evolved in recent years, and reflect on how this is addressed in the current EU policy framework. Conceptual models are available that can help us to structure our thinking and map available evidence to explore this relationship, as well as indicators that focus on the social and environmental dimensions of health and well-being.

A complex challenge

The health and well-being of human societies is intrinsically linked to the quality of the environment in which they live. Over the past century, evidence of the links between toxic, infectious and physical stressors in air, water, soil and food and negative health outcomes for local communities has accumulated. This has driven the implementation of targeted policy actions to address the environmental determinants of health.

This compartmentalised and hazard focused approach continues to deliver significant benefits for health. However, it is inadequate when tackling the multiple stressors and systemic challenges we face today, such as climate change, resource depletion and biodiversity loss. At the same time, our understanding of the human condition has been expanding to capture well-being, as well as health. When considering well-being in relation to the physical environment, it is important to address health stressors, and foster the positive aspects that make for a healthy and stimulating environment.

Recent framing of environment, health and well-being captures multiple and cumulative exposures, upstream drivers and feedback systems over expanded temporal and spatial scales. Health and well-being outcomes are now understood to be embedded in a wider social context, including demographic shifts towards an aging population, urbanisation, lifestyle and consumption changes, and shifts in the global disease burden from communicable to non-communicable disease. For example, shifts in demography and disease burden can increase vulnerability to environmental exposures, while urbanisation and increased consumption can amplify pressures on the environment and erode environmental quality.

These perspectives on the environment, health and well-being nexus aim to capture the dynamic relationships between our use of the environment as a resource, the pressures and resulting exposures that this generates, and resulting effects on human health and well-being. A key challenge in the field of environmental health is how to generate knowledge on these relationships that can inform the development of relevant policy responses.

In this article, we first consider how European Union (EU) policies reflect a more integrated understanding of the environment, health and well-being nexus. We go on to describe the most recent conceptual frameworks used to map these relationships, and identify relevant indicator frameworks. We conclude with some reflections on how frameworks on environment, health and well-being might inform future policy making.

Changing political perspectives

The focus of EU policies on environment and health has shifted from a compartmentalised approach towards a systemic approach that captures the interdependencies across environment, health and well-being challenges.

The Europe 2020 strategy (EC, 2010), the 7th Environment Action Programme (7th EAP) (EU, 2013) and the Roadmap to a Resource-Efficient Europe (EC, 2011) are the EU policy documents that set strategic objectives for the period up until 2020 and longer-term visions up until 2050.

The 7th EAP explicitly focuses on improving environmental quality in order to reap benefits for health and well-being, recognising the need to maintain the capacity of ecosystems to deliver key services essential to human society.

Europe 2020, the EU’s growth strategy for the period 2010 to 2020, presents a vision of a sustainable and inclusive economy, characterised by high levels of employment, productivity and social cohesion. It explicitly acknowledges the need to create synergies between economic and environmental goals, and argues for a transition towards a ‘green economy’. The flagship initiative ‘Resource Efficient Europe’ contains elements relevant to environment and health, where ‘by 2050 the EU’s economy has grown in a way that respects resource constraints and planetary boundaries, thus contributing to a global economic transformation’.

The European Environment and Health Strategy (EC, 2003) took an integrated approach aiming to create synergies between health, environment and research policies. The 2004–2010 Environment and Health Action Plan (EC, 2004) aimed to implement the first cycle of the strategy and focused on the causal links between environmental risk factors and priority diseases.

Effective governance of the environment, human health and well-being reaches across a number of policy domains and must be grounded in an understanding of complex system interactions, feedback loops, and the trade-offs involved. With the aim of facilitating understanding of these systemic risks and interactions, new conceptual frameworks have been developed. The aim is to take an integrated approach to assessing the relationships between environmental factors and human health that can capture the broader spatial, socio-economic and cultural context.

Conceptual approaches

In the field of environmental health, recent efforts have focused on the development of frameworks that can depict the multiple variables at work within the environment, health and well-being nexus and illustrate the causal relationships between them. In particular, the aim has been to capture how drivers catalyse the transition of an environmental state, leading to an exposure that in turn generates a health outcome. The relationship is conceived as bi-directional, whereby high quality environments provide positive impacts on health and well-being. An additional aim is to acknowledge how an individual’s socio-economic context can determine the relationship between exposure and resulting health impacts.

In a parallel development, the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) called for by UN Secretary–General Kofi Annan aimed to assess the consequences of ecosystem change for human well-being and establish the scientific basis for action needed to enhance the conservation and sustainable use of those systems. Work undertaken in this context by the MA Board (MA Board, 2005) recognised the need to place well-being in an ecosystem perspective. Their aim was to capture the dynamic relationships between the ecosystem services provided by natural capital and the key constituents of human well-being.

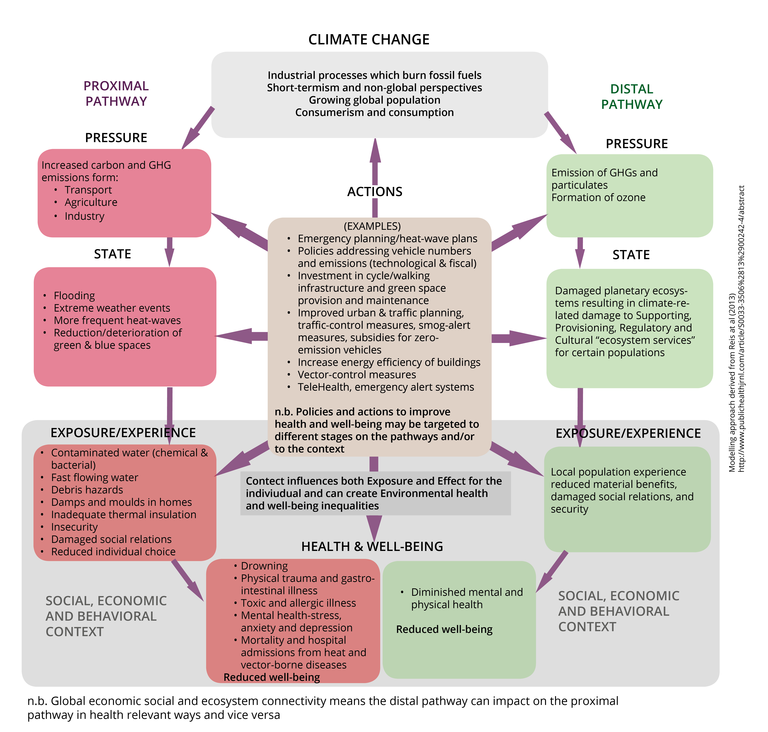

These insights then informed the development of a more recent conceptual model in this field, the Ecosystems Enriched Drivers, Pressures, State, Exposure, Effect, Actions or eDPSEEA model (Reis et al 2013). The distal DPSEEA model presented in figure 1 below, is derived from the eDPSEEA model and depicts a spatially “distal” pathway from drivers to the pressures which disrupt ecosystem services and by extension human health and wellbeing.

Figure 1: The distal DPSEEA model that captures the ecological complexity on environment, health and well-being (EHWB)

Source: Adapted from the Ecosystems Enriched (eDPSEEA model (Reis et al, 2013)

The model recognises this distal pathway through which drivers can influence health and well-being in any location, in addition to the proximal (near in space and time) pathway which is normally considered in environmental public health.

The proximal pathway captures the traditional perspective whereby changes to the local physical environment impact on health and well-being, an example being the effects of contaminated drinking water on the local population.

The second, distal pathway, illustrated above shows how drivers caninfluence health and well-being through their impact on ecosystems services in remote locations. For example, the impacts of greenhouse gas emissions on the global climatic system and resulting climatic disruption at the local level. An important recognition is that, irrespective of where ecosystem damage initially impacts, in a world intimately connected by social, economic and ecological systems, the effects on health and well-being may be felt anywhere, for example through migration or damage to food security.

This conceptual model is attractive since it integrates social complexity with ecological complexity in the relationship between environment, health and well-being over different scales, as well as capturing the positive concept of well-being.

Indicator frameworks

Conceptual frameworks are very useful tools for depicting relationships in systems, but if they are to aid our understanding of the current situation or possible future scenarios, then the relevant parts must be furnished with concrete evidence. Indicators provide a means of organising data on interactions in the system and tracking and communicating trends over space and time.

Traditional economic indicators such as GDP have been criticised for failing to capture important issues which affect human well-being, for example, the state of the environment and the sustainability of economic development. Substantial efforts have been made to develop indicators that address the wider social, health and environmental dimensions of well-being, including the OECD’s Better Life Initiative; the New Economics Foundation’s system of National Accounts of Well-being; the University of Waterloo’s Canadian Index of Well-Being; and Eurostat’s Quality of life indicators.

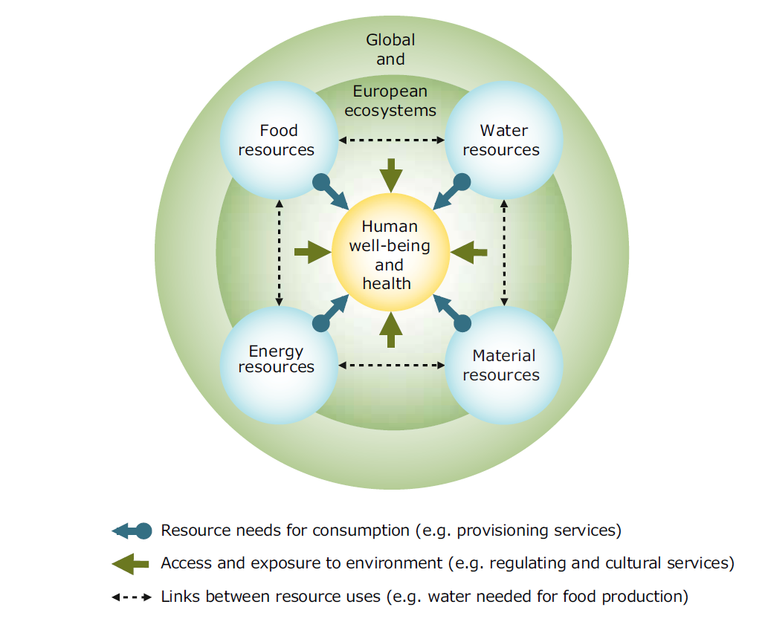

Theuse of natural resources to meet basic needs is also the subject of the Environmental Indicator Report on Natural Resources and Human Well-being in a Green Economy (EEA, 2013). The report takes basic needs as an entry point to resource use, illustrating the complex interdependence of Europe’s systems for meeting its food, water, energy and housing needs (see figure 2 below). The report proposes a suit of indicators that provide insight into resource use patterns and how they impact on the environment and ultimately on human well-being. Although the environmental pressures related to resource use are generally in decline, diverse impacts on human well-being persist due to time lags before improvements in the state of the environment manifest.

Figure 2: Key resource systems and human well-being

Source: EEA, 2013, Environmental indicator report 2013 — Natural resources and human well-being in a green economy.

Tracking multifaceted impacts on health and well-being demands a diverse set of indicators. In developing an indicator base for environment, health and well-being, it is also important to include indicators that combine health, environment and socio-economic dimensions.

In figure 3 below, we take the example of climate change to demonstrate how conceptual mapping can help us to understand the complex relationships between ecosystems, natural, built and social environments, and human health. By identifying the pressures that impact on the state of the environment and determining human exposures and experiences, via both distal and proximal pathways, we can then start to build a portfolio of relevant policy actions.

Figure 3: Addressing the effects and actions of climate change through DPSEEA models

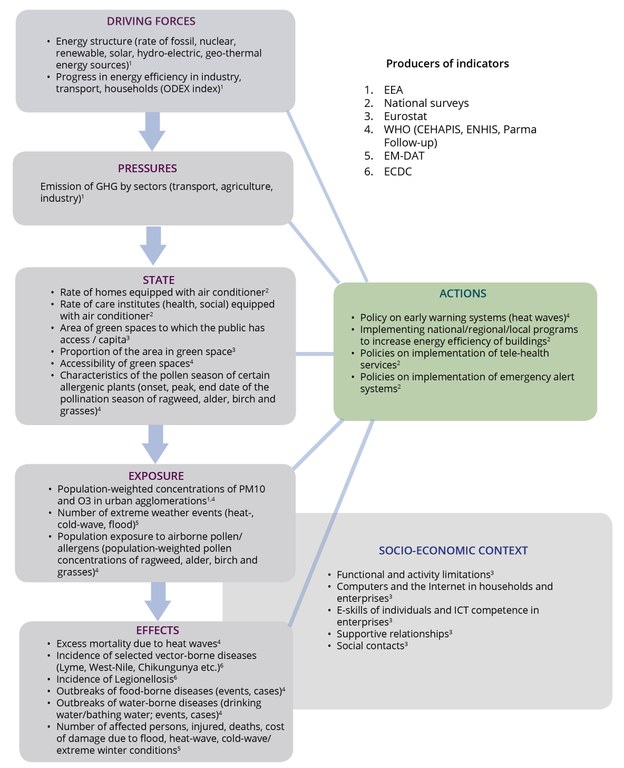

The mapping process enables us to identify indicators that can be used to monitor change at different points in the system, including drivers, pressures, states, exposures, effects and actions. Figure 4 below provides an overview of possible indicators on effects of climate change on the environment and human health, and identifies international data sources that can inform these indicators.

Figure 4: Selected indicators on the effects of climate change on the environment and human health

Looking Forward

Conceptual frameworks can provide tools to think with, allowing us to communicate and bridge gaps across scientific, professional and policy constituencies. The eDPSEEA-model described above permits the broader framing of environment, health and well-being, against which to assemble a diverse array of evidence in a meaningful structure that can provide insights for policy making.

In addition, the framework allows us to configure a set of assessment indicators which reflect the social and ecological complexity of environment, health and well-being and can be used to track the effectiveness of policy, the interactions between several policy measures and unintended health consequences of policies. A challenge remains in terms of the availability of data with which to furnish indicators in the environment, health and well-being nexus. Relevant data are in some cases available from international or national data sources, but spatial and temporal coverage is fragmented. The further development of an indicator system for environment, health and well-being should be coupled with improvements in the evidence base in order to effectively inform future policy initiatives.

References

Canadian Index of Well-being. University of Waterloo, Faculty of Applied Health Sciences., Waterloo, Ontario, available at: https://uwaterloo.ca/canadian-index-well-being

EC, 2003, Communication from the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament and the European Economic and Social Committee – A European Environment and Health Strategy. COM/2003/0338

EC, 2004, Communication from the Commission: The European Environment & Health Action Plan 2004-2010. COM(2004) 416

EC, 2010, Communication from the Commission – Europe 2020 – A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. COM(2010) 2020EC, 2011, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions — Roadmap to a Resource Efficient Europe, COM/2011/571

EEA, 2013, Environmental indicator report 2013 — Natural resources and human well-being in a green economy, European Environment Agency, Copenhagen.

EU, 2013, Decision No 1386/2013/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 November 2013 on a General Union Environment Action Programme to 2020 ‘Living well, within the limits of our planet’, COD 2012/0337

Eurostat, Quality of life indicators, Eurostat. Available at: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/statistics_explained/index.php/Quality_of_life_indicators

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2013.07.006

Indicators of Well-being in Canada. Employment and Social Development Canada. Available at: http://www4.hrsdc.gc.ca/[email protected]

MA Board, 2005, Ecosystems and human well-being. Available at: http://www.unep.org/maweb/documents/document.354.aspx.pdf

National Accounts of Well-being. New Economics Foundation. Available at: http://www.nationalaccountsofwell-being.org/explore/indicators/zwbi

OECD. OECD Better Life Index. Available at: http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=BLI

Reis S, et al., 2013, Integrating health and environmental impact analysis, Public Health.

WHO (2013).Joint meeting of experts on targets and indicators for health and well-being in Health 2020 Copenhagen, Denmark, 5–7 February 2013. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/186024/e96819.pdf?ua=1

This article presents a summary of work undertaken for the European Environment Agency (EEA) by the FRESH Consortium, a collaboration of EEA National Reference Centres and independent experts. The FRESH Consortium includes: Anna Paldy and Tibor Malnasi, NIEH, Hungary; Adrienne Pittman, Salma Elreedy, Louis Laurent, Jean-Nicolas Ormsby, ANSES, France; George Morris, United Kingdom; Natasa Kovac, EA, Slovenia; Brigit Staatsen (coordinator), Wim Swart, RIVM, the Netherlands; Dragan Gjorgjev, RIPH, Macedonia; Dave Stone, Natural England, United Kingdom; Judith Meierrose, Marianne Rappolder UBA, Germany; Peter Otorepec, Ana Hojs, NIPH, Slovenia; Michele Rasoloharimahefa, Catherine Bouland, ULB, Belgium; and Natasa Janev, NIPH, Croatia.